Imagine a world teetering on the brink of financial collapse, where the very arteries of global commerce, international credit and liquidity are seizing up. In such moments of profound uncertainty, a largely unheralded yet immensely powerful mechanism springs into action: Central Bank Swap Lines.

Central bank swap lines aren’t just classical financial instruments, they are the emergency lifelines that connect the world's most influential central banks, allowing them to instantly exchange currencies when panic threatens to dry up liquidity and funding.

Introduction

Central bank swap lines represent a critical instrument in the architecture of global financial stability, facilitating the temporary exchange of currencies between national monetary authorities.

These arrangements, fundamentally a sophisticated form of currency swap, are often structured as repurchase agreements (repos), where one currency is loaned against another as collateral. For instance, if the European Central Bank (ECB) requires U.S. dollars, the Federal Reserve (Fed) provides these dollars, with the ECB offering an equivalent value of Euros as security.

The core function of these swap lines is to inject liquidity in a specific currency, predominantly the U.S. dollar, into foreign financial systems. This is achieved indirectly, as the dollars are channeled through the foreign central bank, which then typically auctions them to commercial banks within its jurisdiction.

From the Federal Reserve's perspective, swap lines are strategically deployed to safeguard the flow of credit to U.S. households and businesses. This is accomplished by mitigating risks to U.S. financial markets that may arise from financial stress originating abroad. By fostering stability in foreign dollar markets, these swap lines inherently contribute to the U.S. economy through enhanced market confidence and robust trade channels.

This evolution reflects a significant expansion of the central bank's traditional role. Historically, a central bank's primary duty has been to serve as a domestic lender of last resort, providing emergency liquidity to its own financial system. However, the very design and operational purpose of central bank swap lines demonstrate a clear extension of this function beyond national borders, and through these mechanisms, the Federal Reserve effectively assumes the role of a de-facto international lender of last resort for the global dollar funding market.

The broadening of the Fed role as the international lender of last resort is a direct consequence of the profound interconnectedness of contemporary global finance, where financial dislocations in one region can rapidly spill over and impact domestic markets. This implies that the Fed's mandate, while nominally focused on domestic objectives, must, by necessity, encompass the management of global dollar liquidity to achieve its core goals.

Moreover, the Federal Reserve primarily established swap lines to address severe liquidity pressures in U.S. dollar funding markets located overseas. Such difficulties in foreign dollar markets possess the capacity to materially intensify strains in funding and credit markets both within the United States and across the broader global economy. These arrangements are indispensable for enhancing liquidity conditions in both domestic U.S. and international financial markets. They achieve this by empowering foreign central banks to supply U.S. dollar funding to institutions under their oversight during periods of acute market stress.

The Fed's network of standing swap lines, which has been a permanent fixture in the international monetary system since 2013, serves as a routine policy tool, and its design aims to proactively diminish risks to U.S. financial markets that could emanate from financial turbulence abroad.

Furthermore, the establishment of these standing arrangements in 2013, and their activation on a precautionary basis, signifies a strategic shift from purely reactive crisis intervention to a more proactive and permanent mechanism for ensuring global financial stability, and the readiness to deploy these lines, even in the absence of immediate severe stress, serves to calm markets and prevent potential future dislocations.

This evolution in policy reflects a sophisticated understanding of systemic risk within a highly globalized financial system, suggesting that central banks now perceive global dollar funding issues not merely as episodic crises, but as a persistent structural vulnerability that necessitates continuous monitoring and the availability of readily accessible, institutionalized mechanisms for liquidity provision, rather than relying solely on ad-hoc responses to acute emergencies.

Historical Context and Evolution of Central Bank Swap Lines

The emergence and evolution of central bank swap lines are deeply rooted in the historical challenges of international monetary management, particularly the enduring quest for exchange rate stability and sufficient global liquidity.

Pre-Bretton Woods Global Financial Arrangements

Before the outbreak of World War I, the international monetary system was predominantly characterized by the international gold standard. Under this system, gold served as the primary international reserve asset, and the values of national currencies were rigidly fixed by their declared par value in gold. This framework was conceived to foster relatively free trade and payments across the globe.

However, the interwar period, especially the 1930s, plunged the world into profound economic instability. This era was marked by widespread competitive devaluations and a significant contraction of international trade, largely stemming from pervasive uncertainty regarding currency values. Nations responded by hoarding gold and any money that could be converted into gold, which further exacerbated the decline in global monetary transactions.

In a direct response to the volatility and economic devastation of the 1930s, the Bretton Woods system was forged in July 1944, with the aim to avoid the rigidity that had characterized the gold standard while promoting greater international cooperation. The system ultimately adopted at Bretton Woods, led to the establishment of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank.

The Bretton Woods system introduced a pegged but adjustable exchange rate system, with the U.S. dollar uniquely fixed to gold at $35 per ounce. Other member countries, in turn, pegged their currencies to the dollar, allowing for only a narrow 1% band of variation, and the cornerstone of this new system was the U.S. government's commitment to exchange gold for dollars at this fixed rate upon demand.

The gold standard, while providing a degree of stability, proved inflexible in generating adequate liquidity growth to support expanding global trade. Bretton Woods attempted to address this by anchoring the system to the U.S. dollar, but it too encountered inherent limitations related to liquidity and confidence, thereby setting the stage for the eventual necessity of more flexible tools such as central bank swap lines.

Swap lines represent a pragmatic evolution in this continuous quest, emerging as a crucial liquidity mechanism when previous, more rigid frameworks proved inadequate in managing the dynamic interplay between stability and liquidity within a progressively integrated global economy.

The 1960s U.S. Gold Crisis and the Rise of Dollar Liabilities

Despite its ambitious design, the Bretton Woods system was plagued by inherent "liquidity problems" and a pervasive "confidence problem".

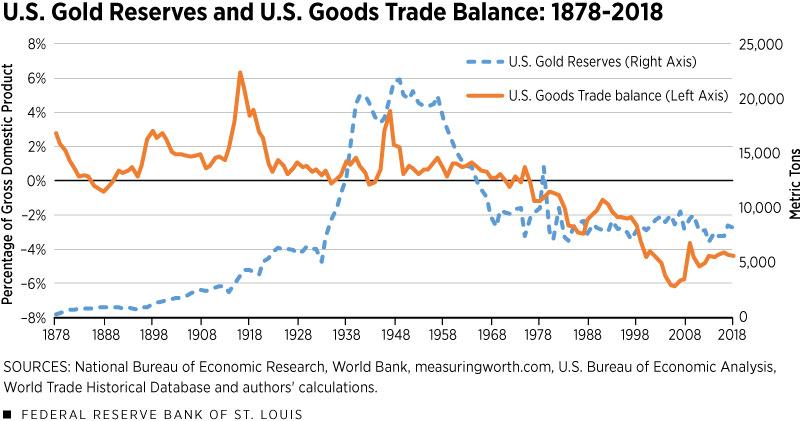

A key structural flaw became evident in the 1960s: the global supply of gold, which was the system's designated primary reserve asset, grew at a sluggish annual rate of merely 1-1.5%. In stark contrast, global trade was expanding at a much more rapid pace, approximately 7% per year. This widening disparity led to an increasing shortage of international reserves, straining the system's capacity.

A critical vulnerability emerged as U.S. dollar liabilities held by non-U.S. central banks began to significantly exceed the U.S. official gold stock. For example, by the close of 1967, U.S. gold reserves amounted to $12.8Bn, while dollar liabilities had swelled to $34.04Bn. This growing imbalance created a profound "confidence problem," as it became increasingly apparent that the U.S. could not fulfill its commitment to meet all demands if foreign central banks simultaneously sought to convert their substantial dollar holdings into gold.

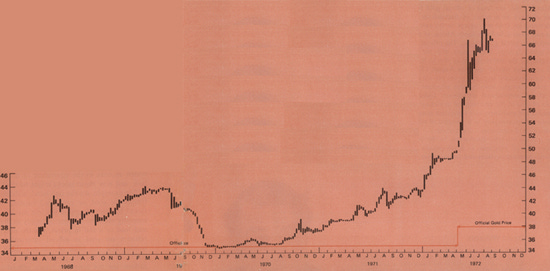

Intensifying speculative pressures, coupled with actions by some countries, to convert their dollar holdings into gold, further exacerbated the crisis. The mounting pressure on gold prices eventually necessitated the establishment of a "two-tier gold market" in 1968.

Under this new arrangement, transactions between central banks continued at the official $35 per ounce price, while private markets were allowed to operate at a floating price determined by supply and demand.

The increasing discrepancy between U.S. dollar liabilities and its gold reserves, combined with the erosion of confidence in the dollar's convertibility, vividly illustrates Robert Triffin's Dilemma.

To provide the necessary liquidity for expanding global trade and finance, the United States was compelled to run persistent balance-of-payments deficits. This process, however, simultaneously increased the volume of foreign-held dollars, thereby undermining confidence in the dollar's convertibility to a finite gold supply and creating an inherent instability within the system.

The gold crisis was a direct and, in many respects, inevitable consequence of this fundamental design flaw. It compelled the U.S. to seek innovative tools to defend the Dollar-Gold peg and ultimately contributed to the abandonment of gold convertibility in August 1971. This pivotal event ushered in an era of floating exchange rates and fundamentally reshaped the landscape for international monetary policy, significantly increasing the demand for flexible liquidity tools like swap lines in a post-Bretton Woods global financial environment.

Creation of Swap Lines in 1962/1965 as a Response to Instability

In direct response to the escalating pressures on the U.S. dollar and the gold crisis, the Federal Reserve initiated the development of central bank swap lines in 1962. This marked the rapid establishment of a network involving key Western central banks and the Bank for International Settlements (BIS).

The network expanded swiftly, growing from approximately $2 billion by the end of 1963 to $10 billion by the end of 1969, and further to $30 billion by 1978. By August 1971, the total value of these arrangements had reached $11.7 billion, encompassing 14 central banks.

As well, the primary objective of these nascent swap lines was to stabilize the U.S. dollar exchange rate against temporary fluctuations and to help safeguard the value of the dollar in the international exchange markets, and they were widely regarded as a crucial perimeter defence line shielding the dollar against speculation and other exchange market pressures.

The Fed employed these lines to provide foreign central banks with a mechanism to manage unwanted, temporary accumulations of dollars. Furthermore, they supplied these central banks with dollar funds to finance their own market interventions, effectively serving as a delayed tactic against the continuous drain of the U.S. gold stock.

The establishment of swap lines in the early 1960s directly correlates with the intensifying U.S. gold crisis and the burgeoning volume of dollar liabilities. Their explicitly stated purpose was to "defend the official gold peg" and to "forestall claims on U.S. gold reserves". This indicates that swap lines were not initially conceived as a fundamental solution to the inherent flaws of the Bretton Woods system. Rather, they were a tactical, short-term tool designed to manage the system's symptoms, buy time, and prolong its viability in the face of mounting speculative and structural pressures.

Evolution Through Major Crises

Central bank swap lines have demonstrated remarkable adaptability, evolving significantly in response to major global financial crises.

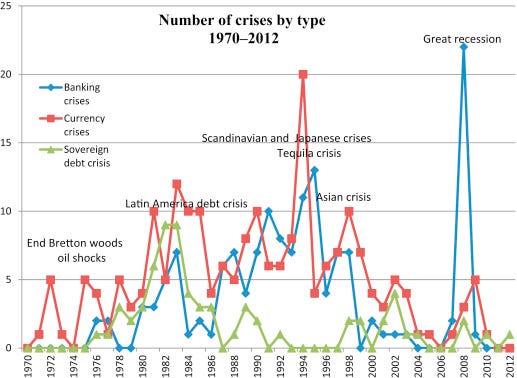

1970s Oil Shocks and Monetary Instability

The 1970s marked a period of profound global monetary instability, punctuated by two significant oil shocks in 1973-74 and 1978-79. The 1973 OPEC oil embargo, in particular, triggered a nearly 300% increase in oil prices, quadrupling them by 1974.

This dramatic surge profoundly complicated the macroeconomic environment and fuelled widespread global inflation. The devaluation of the dollar in the early 1970s (1971 and 1973), following the effective end of the Bretton Woods agreement, was also a central factor in the oil price increases, as OPEC nations sought to maintain the real value of their oil revenues.

While the Federal Reserve's primary policy focus during the 1970s shifted aggressively towards combating rising inflation, swap lines continued to play a role in managing currency fluctuations and providing short-term credits. For instance, the Fed actively intervened in foreign exchange markets, selling German marks and Swiss francs, often drawn from swap lines, to cushion the dollar's decline and stabilize exchange rates. The Fed also provided short-term assistance to central banks such as the Bank of Italy, Bank of Mexico, and Bank of England through existing swap arrangements.

The initial purpose of swap lines was to defend the U.S. dollar's gold peg under the Bretton Woods system. However, the 1970s witnessed the collapse of Bretton Woods and the advent of floating exchange rates, alongside severe inflationary pressures from oil shocks. Despite this fundamental systemic shift, the evidence indicates that swap lines remained a relevant tool, employed for managing currency volatility and providing crucial bridge loans during crises.

The continued and adapted use of swap lines in the turbulent post-Bretton Woods era highlights that their fundamental value lies in providing a flexible, rapid-response mechanism for cross-border liquidity and exchange rate management. This adaptability cemented their position as a critical, enduring tool in the international monetary toolkit, capable of addressing diverse financial challenges regardless of the prevailing exchange rate system.

The 2008 Global Financial Crisis

The 2008 financial crisis exposed profound U.S. dollar funding shortages in overseas markets, particularly affecting European banks that had become heavily reliant on U.S. money markets. This led to significant disruptions in foreign exchange (FX) swap markets and severely illiquid trading conditions. In response, the Federal Reserve rapidly established and expanded dollar liquidity swap lines, commencing in December 2007 with initial agreements with the European Central Bank (ECB) and the Swiss National Bank (SNB).

Following the dramatic collapse of Lehman Brothers in September 2008, the Fed significantly broadened its swap line network to include 12 additional central banks. It eventually granted unlimited dollar access to the ECB, SNB, Bank of England (BoE), and Bank of Japan (BoJ). The aggregate peak outstanding amount of swaps reached an unprecedented $583 billion by December 2008. These lines proved instrumental in channeling emergency dollar liquidity to foreign depository institutions that lacked direct access to the Fed's own borrowing facilities.

The sheer scale, rapid expansion, and provision of "unlimited dollar access" through the Fed's swap lines during the 2008 Global Financial Crisis , in direct response to a pervasive global dollar shortage , transcended mere international cooperation. This effectively positioned the Federal Reserve as the international lender of last resort for the world's dominant currency.

The extensive intervention was not solely about providing assistance to foreign economies; it was also strategically aimed at protecting the U.S. economy from severe spillover effects., further highlighting the profound interconnectedness of global financial markets and the recognition that domestic stability is inextricably linked to global stability.

The 2008 crisis unequivocally demonstrated a critical gap in the existing global financial safety net that traditional institutions like the IMF could not address with the necessary speed or scale. The success of the swap lines in mitigating systemic risk provided a powerful empirical justification for their continued and expanded use, establishing a precedent for the Fed's role as the ultimate backstop for the global dollar funding market, irrespective of ongoing debates regarding its statutory authority.

The COVID-19 Pandemic

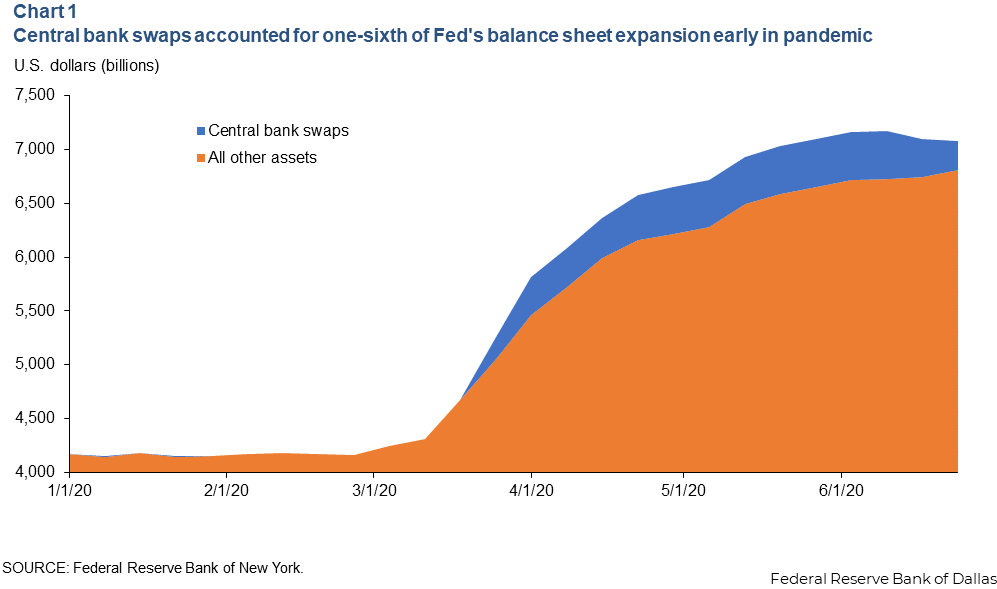

The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in early 2020 triggered immediate and severe strains in global U.S. dollar funding markets. This period was characterized by a widespread "dash for cash" and a sharp increase in offshore dollar funding costs.

In a rapid and coordinated response, the Fed and other major central banks swiftly reactivated and enhanced the terms of the standing swap network. Key enhancements included lowering the interest rate by 25 basis points to the U.S. overnight index swap (OIS) rate plus 25 bps, and introducing 84-day maturities in addition to the existing seven-day terms.

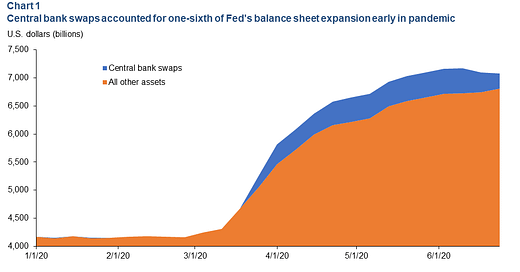

Furthermore, temporary, capped dollar swap lines were established with nine additional central banks, effectively reinstating the same list of 14 countries that had received Fed swap lines during the 2008 Global Financial Crisis. Outstanding swap line borrowing peaked at $449 billion during the week of May 27, 2020, with the European Central Bank and Bank of Japan being the primary borrowers. These interventions proved highly effective in reducing mis-pricing in FX markets and providing crucial cross-border liquidity.

The swift and coordinated response to the COVID-19 pandemic, including the rapid activation and enhancement of existing swap lines and the re-establishment of temporary ones, demonstrated a profound institutionalization of these mechanisms within the global financial safety net.

The ability to quickly deploy these tools, with pre-agreed terms and established relationships, allowed central banks to act decisively to calm markets and prevent severe dislocations. This pre-emptive and systematic approach, building on lessons from the 2008 crisis, indicates that swap lines are no longer merely ad-hoc crisis tools but have become a permanent, indispensable feature of global liquidity management. Their readiness and predictable availability contribute significantly to market confidence, often stabilizing conditions even before substantial amounts are drawn.

Operational Mechanics of Central Bank Swap Lines

The effectiveness of central bank swap lines hinges on their clearly defined operational mechanics, which facilitate rapid and efficient cross-border liquidity provision.

Agreement Structure and Transaction Steps

A central bank swap line is fundamentally an agreement between two central banks for the temporary exchange of currencies. These arrangements are typically structured as repurchase agreements (repos), where a loan in one currency is collateralized by another currency.

The operation generally involves two distinct transactions. In the first transaction:

a foreign central bank draws on its swap line with the Federal Reserve by selling a specified amount of its own currency to the Fed in exchange for U.S dollars at the prevailing market exchange rate.

The Federal Reserve then holds this foreign currency in an account at the foreign central bank.

Concurrently, the dollars provided by the Fed are deposited into an account that the foreign central bank maintains at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

Simultaneously with the initial exchange, both central banks enter into a binding agreement for a second transaction:

This obligates the foreign central bank to buy back its currency on a specified future date, using the same exchange rate as in the first transaction.

This second transaction effectively unwinds the first. At the conclusion of this second transaction, the foreign central bank pays interest to the Federal Reserve, typically at a market-based rate.

Dollar liquidity swaps generally have maturities ranging from overnight to three months.

Once the foreign central bank obtains the U.S. dollars by drawing on its swap line, it determines the terms on which it will lend these dollars onward to institutions within its own jurisdiction. This includes deciding which institutions are eligible to borrow and what types of collateral they must provide. A crucial aspect of this structure is that the Federal Reserve's contractual relationship is exclusively with the foreign central bank, not with the individual financial institutions that ultimately receive the dollar funding. Consequently, the Federal Reserve does not assume the credit risk associated with lending to institutions based in foreign jurisdictions, nor is it exposed to movements in foreign exchange rates, as the swap is unwound at the same exchange rate used in the initial draw.

Key Participants and Coordination

Above infographic credit goes to

The Federal Reserve maintains a core network of standing central bank liquidity swap lines with five major central banks: the Bank of Canada, the Bank of England, the Bank of Japan, the European Central Bank, and the Swiss National Bank. These standing arrangements allow for the provision of liquidity in any of the six currencies (U.S. dollars, Canadian dollars, Sterling, Yen, Euros, and Swiss Francs) should market conditions warrant.

During periods of heightened global financial stress, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, the Federal Reserve has expanded its network by establishing temporary swap arrangements with additional central banks. For instance, during the COVID-19 crisis, temporary lines were set up with nine other central banks:

the Reserve Bank of Australia, the Banco Central do Brasil, Danmarks National bank (Denmark), the Bank of Korea, the Banco de Mexico, the Reserve Bank of New Zealand, the Norges Bank (Norway), the Monetary Authority of Singapore, and the Sveriges Riksbank (Sweden).

These temporary arrangements often mirror the list of countries that received Fed swap lines during the 2008 Global Financial Crisis.

Differentiating Temporary from Standing Arrangements

A key distinction in the operation of central bank swap lines lies between temporary and standing (or permanent) arrangements.

Temporary arrangements are characterized by a defined termination date and are typically established in response to specific, acute periods of market stress or crisis. For example, the initial dollar liquidity swap lines authorized by the FOMC in December 2007 during the Global Financial Crisis were temporary and terminated on February 1, 2010. Similarly, the temporary swap lines established during the COVID-19 pandemic with nine additional countries concluded in December 2021.

In contrast, standing arrangements are designed to remain in place indefinitely, typically "until further notice". The temporary dollar liquidity swap arrangements with the Bank of Canada, Bank of England, European Central Bank, Bank of Japan, and Swiss National Bank were converted to standing arrangements in October 2013. This conversion signifies a fundamental shift in their role: from ad-hoc crisis intervention tools to a permanent liquidity backstop for key international partners.

The conversion of temporary swap arrangements to standing facilities in 2013 signifies a profound shift in the understanding and application of these tools. It marks a move from viewing swap lines as merely ad-hoc interventions to a recognition of their role as a structural component of global finance. This institutionalization reflects an acknowledgment of the U.S. dollar's persistent and pervasive role in global finance and the ongoing necessity for a robust, readily available liquidity backstop.

Impact on Global Financial Stability and Monetary Policy

Central bank swap lines have exerted a profound and multifaceted impact on global financial stability and the conduct of international monetary policy, particularly during periods of acute stress.

Role in Preventing Liquidity Shortages and Market Dysfunction

A primary contribution of central bank swap lines is their capacity to significantly improve dollar funding conditions both globally and within the United States. They are specifically designed to alleviate market dysfunction by reducing the reliance of dollar-constrained institutions on the foreign exchange (FX) market for their dollar funding needs. By providing an alternative, reliable source of liquidity, swap lines enable top-tier banks to borrow dollars at rates close to the risk-free rate, which in turn facilitates their ability to engage in arbitrage and lend in the FX market.

A key indicator of their effectiveness is their impact on covered interest rate parity (CIP) violations. These deviations often serve as a proxy for the scarcity of dollar liquidity in cross-border markets. Research consistently shows that swap line interventions reduce both the level and volatility of CIP violations, indicating a direct alleviation of dollar funding stresses. The provision of these lines acts as a "prudent liquidity backstop," easing strains in financial markets and mitigating their adverse effects on broader economic conditions.

Case Study: The 2008 Global Financial Crisis

The 2008 Global Financial Crisis served as a stark demonstration of the indispensable role of central bank swap lines. The crisis was characterized by severe U.S. dollar funding shortages that threatened to cripple the global financial system. In response, the Federal Reserve rapidly established and expanded its dollar liquidity swap lines, beginning in December 2007 with agreements with the European Central Bank and the Swiss National Bank. Following the collapse of Lehman Brothers, the network expanded dramatically, eventually providing unlimited dollar access to major central banks like the ECB, SNB, Bank of England, and Bank of Japan. The peak outstanding amount of swaps reached an unprecedented $583 billion by December 2008. These interventions were critical in addressing the acute dollar shortages faced by European banks and were widely considered a "decisive innovation" in the crisis response, preventing a potentially much more severe global dollar funding crisis.

Case Study: The COVID-19 Pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic, beginning in early 2020, triggered another period of intense global dollar funding stress, marked by a "dash for cash" and a sharp increase in offshore dollar funding costs. The response built upon the 2008 experience, with the Fed and other major central banks swiftly reactivating and enhancing the terms of the standing swap network. Key enhancements included lowering the interest rate and introducing longer maturities. Temporary, capped dollar swap lines were also re-established with nine additional central banks, mirroring the 2008 network.

Outstanding swap line borrowing peaked at $449 billion in May 2020. These actions proved highly effective in stabilizing markets, stopping the widening of swap basis spreads, and even leading to their narrowing. They were crucial for maintaining credit flows globally and in the U.S..

Effects on Foreign Exchange Markets, Banking Liquidity, and Investor Confidence

The impact of swap lines extends across several dimensions of financial markets. They have demonstrably reduced volatility and mis-pricing in foreign exchange markets. By providing a direct channel for dollar liquidity, they increase the net supply of dollars to non-financial institutions, which might otherwise struggle to obtain funding. This, in turn, lowers funding costs for banks and facilitates increased lending to firms across borders. The announcement and subsequent operations of swap lines have also been linked to the appreciation of partner currencies against the U.S. dollar and a reduction in the cross-currency basis, signaling improved liquidity conditions.

Beyond the direct provision of liquidity, a significant aspect of central bank swap lines is their powerful signaling effect and their capacity to bolster confidence. The mere announcement and perceived availability of these swap lines, even before substantial amounts are drawn, can have a profound calming effect on markets. This occurs because such announcements signal robust central bank cooperation and a firm commitment to providing necessary liquidity. This assurance helps to alleviate market participants' fears of severe dollar shortages, thereby reducing uncertainty and fostering a return to more orderly market functioning. This goes beyond a simple mechanical injection of liquidity; it demonstrates that the psychological dimension of market confidence is a critical channel through which swap lines exert their influence. The knowledge that a credible backstop exists can prevent illiquidity from spiraling into insolvency, underpinning overall financial stability.

Criticisms and Geopolitical Considerations

Despite their demonstrated effectiveness in crisis management, central bank swap lines are not without their criticisms and carry significant geopolitical implications.

Potential Moral Hazard

The role of central banks as lenders of last resort (LOLR) is inherently controversial, largely due to the potential for creating moral hazard on a massive scale. Critics argue that by providing emergency liquidity, particularly to foreign financial institutions or even entire monetary systems, swap lines might inadvertently encourage excessive risk-taking by these entities, under the expectation of future bailouts. This raises a fundamental debate: were these lending facilities crucial in preventing a global depression, or did they sow the seeds of future crises by fostering a perception of implicit guarantees?

To mitigate moral hazard, some argue for strong conditionality attached to liquidity support. Another challenge is the stigma often associated with borrowing from central bank emergency facilities, which can impede their effective use. While market-wide facilities used regularly might reduce this stigma, new disclosure requirements could potentially exacerbate it. The inherent tension lies in balancing the imperative of providing necessary liquidity during crises with the risk of fostering reckless behavior. The challenge for policymakers is to design mechanisms that are effective in stabilizing markets without creating undue reliance or signaling weakness that could encourage imprudent financial practices.

Dependency on U.S. Dollar Liquidity

The global financial system exhibits a profound reliance on the U.S. dollar, a dependency particularly evident for eurozone banks, with approximately 17% of their funding sourced in U.S. dollars and €1.6 trillion in greenback-denominated assets in repo markets alone. This asymmetric power dynamic means the Federal Reserve, as the issuer of the world's primary reserve currency, effectively controls global dollar liquidity, thereby granting the U.S. an outsized influence over international financial stability.

This dependency has given rise to significant concerns about the potential "weaponization" of dollar access in geopolitical or trade disputes. There are anxieties that a future U.S. administration might decline to extend swap line credit for political reasons, potentially leaving dependent nations vulnerable.

Furthermore, the U.S. dollar's dominance, often referred to as its "exorbitant privilege," while undeniably providing significant economic and financial benefits to the United States, also represents a double-edged sword with profound geopolitical implications. While it allows the U.S. to finance its deficits more easily and provides a safe haven during crises, it simultaneously creates a structural vulnerability for other nations reliant on dollar liquidity. The perception that dollar access could be used as a tool of U.S. foreign policy, particularly through sanctions or political conditionality, fuels efforts by other countries, including strategic rivals like China and Russia, and even allies like those in the Eurozone, to reduce their reliance on the dollar. This dynamic underscores the inherent tension between the economic benefits of currency dominance and the geopolitical risks associated with its leverage.

Concerns Over Fairness in Distribution and Emerging Market Exclusion

A significant criticism levelled against the current central bank swap line architecture concerns its fairness and inclusivity, particularly regarding emerging market and developing economies (EMDEs). Research indicates that advanced economies (AEs) are considerably more likely to receive swap lines, even during crises, suggesting a prioritization of wealthier nations. This selective access means that middle-income and low-income countries are often excluded from this vital component of the Global Financial Safety Net (GFSN), leaving them without adequate support during periods of financial distress. The Federal Reserve, as the primary provider of dollar swap lines, has also faced criticism for its lack of transparency regarding the eligibility criteria for these arrangements.

The selectivity inherent in the current central bank swap line framework reinforces existing global financial inequalities. By predominantly extending access to advanced economies, even during periods of widespread financial turmoil, the system effectively prioritizes wealthier nations, potentially leaving more vulnerable economies without adequate liquidity support when they need it most. This unequal architecture raises fundamental questions about the inclusivity and fairness of global financial support mechanisms, highlighting a significant gap in the global financial safety net that disproportionately affects countries with fewer resources and greater susceptibility to external shocks.

Geopolitical Issues: The U.S. Dollar's Role in Global Trade and Reserve Currency Dominance

The U.S. dollar's preeminent position in the international monetary system is undeniable. As of 2024, approximately 58% of global central bank reserves were held in dollar-denominated assets, and 54% of global exports are invoiced and settled in dollars. Furthermore, the dollar is involved in an impressive 88% of all currency trades, cementing its role as a dominant vehicle currency in foreign exchange markets. This dominance confers substantial economic and financial advantages to the United States, including lower borrowing costs, reduced currency hedging expenses for U.S. exporters and importers, and easier access to foreign goods for U.S. consumers.

However, this "exorbitant privilege" also carries geopolitical ramifications. The repeated use of the dollar and its associated payment systems as a tool for imposing economic sanctions on countries whose actions do not align with U.S. interests has been a consistent feature of U.S. foreign policy since the Cold War era. This perceived "weaponisation" of the dollar has increasingly incentivised other nations, particularly strategic rivals like China and Russia, to pursue "de-dollarization" efforts in their economic relations. Even U.S. allies, such as European countries, have recognized the importance of developing independent financial systems to reduce their vulnerability to potential U.S. unilateral decisions. The BRICS nations, representing a significant portion of the global economy and population, are actively pursuing de-dollarization strategies, signaling a growing trend towards diversification away from the dollar.

The perceived weaponization of the dollar by the United States is accelerating efforts by other nations to reduce their reliance on it, and this dynamic is driven by a desire to mitigate geopolitical risks and enhance financial autonomy. Such efforts, if successful, could lead to a more fragmented international monetary system, potentially diminishing the dollar's long-standing dominance and altering global power dynamics. This poses a long-term challenge to the existing financial architecture, prompting debates about the future role of the dollar and the need for more diversified reserve currency options.

Future Challenges and Potential Reforms

The evolving global financial landscape necessitates a continuous reassessment of central bank swap lines, focusing on expanding their reach, exploring multilateral alternatives, and addressing future challenges.

Expanding Swap Agreements to Emerging Markets

Bilateral central bank swap agreements have emerged as the most significant source of emergency liquidity since the 2008 financial crisis, often exceeding the volumes of short-term financing available through regional financial agreements (RFAs) and the IMF.

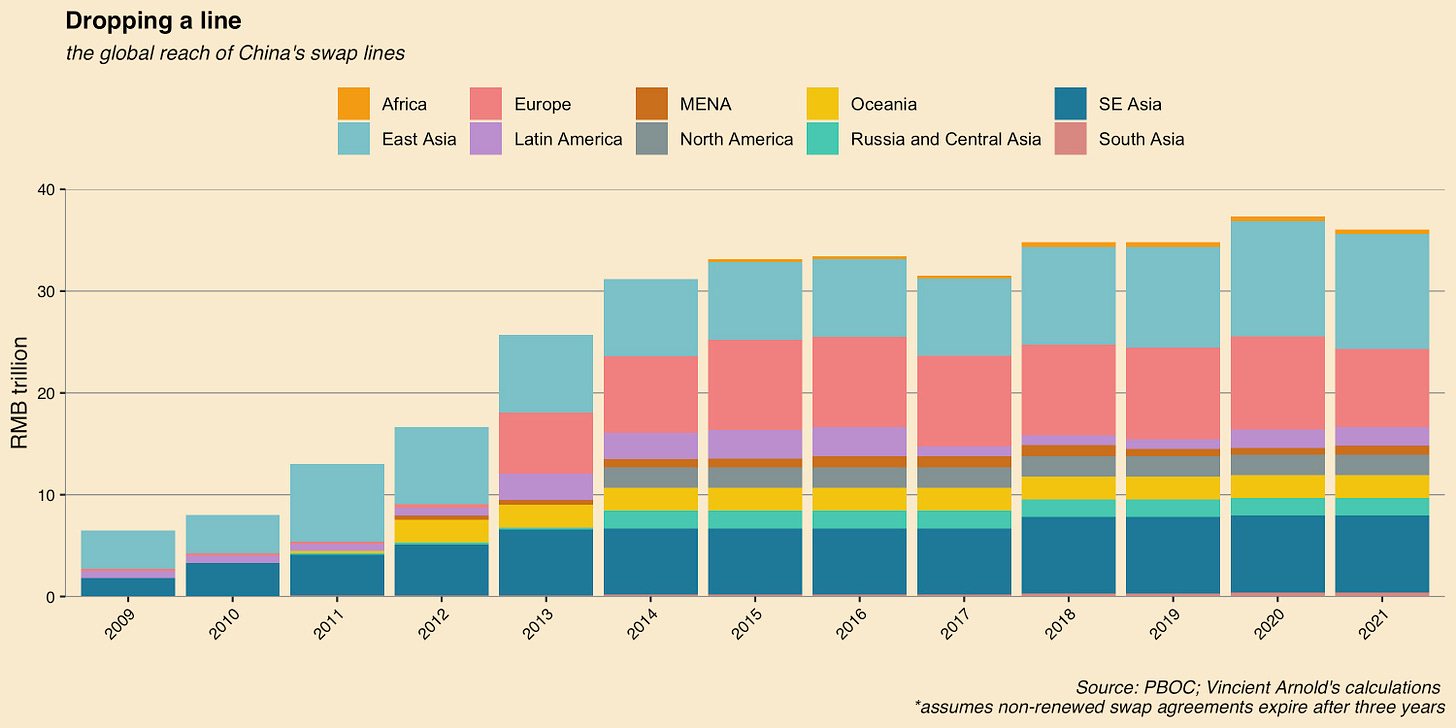

The People's Bank of China (PBOC), for instance, has developed a growing swap network, which some borrowing countries have utilized for macroeconomic crisis support, offering what is perceived as an alternative to the strict conditionalities often imposed by the IMF.

There are growing proposals for expanding the Federal Reserve's swap lines, its Foreign and International Monetary Authorities (FIMA) Repo Facility, or the European Central Bank's EUREP facility to include more countries, particularly emerging markets. Concurrently, discussions around IMF reforms aim to strengthen the global financial safety net for emerging market and developing economies (EMDEs). Proposed changes include revamping the role of Special Drawing Rights (SDRs) and delinking quotas and resource contributions from lending, all to enhance liquidity provision for vulnerable countries.

There is a growing recognition that the current selective nature of central bank swap lines leaves many vulnerable economies exposed to liquidity shocks. The disproportionate access for advanced economies, as discussed previously, highlights a significant gap in the global financial safety net. This necessitates reforms to broaden access to liquidity, ensuring that a wider range of countries can benefit from these crucial backstops during times of financial distress. The expansion of swap agreements to emerging markets is seen as a vital step towards creating a more inclusive and resilient global financial architecture.

Transitioning Toward a More Multilateral Currency Arrangement

The rise of bilateral swap networks, while effective in addressing specific liquidity needs, represents a divergence from the multilateral ideals that underpinned the Bretton Woods institutions. While China's PBOC swaps offer an alternative, they are not a full substitute for IMF financing due to factors such as shorter duration, varying costs, limited financing amounts, and their denomination in Renminbi (RMB), which is less easily convertible than other major currencies. However, PBOC swap lines do play a valuable complementary role, serving as bridge loans to secure IMF programs or as supplementary financing to bolster existing ones.

Beyond bilateral arrangements, there have been efforts towards more multilateral swap initiatives. Examples include the Chiang Mai Initiative Multilateralization (CMIM) in Asia and the BRICS Contingent Reserve Arrangement, both designed to provide standing facilities for multilateral currency swaps. These initiatives reflect a desire for pooled resources and collective self-insurance among groups of nations. There are also calls for the development of internationally agreed principles for the use of swap lines to ensure a fairer and potentially more efficient application of these instruments.

The proliferation of bilateral swap networks, while effective in specific contexts, introduces a tension with the multilateral framework of global financial governance. The shift towards more direct, country-to-country liquidity arrangements challenges the universality and conditionality typically associated with institutions like the IMF. This dynamic prompts ongoing debates about whether the global financial architecture should move towards a more coordinated, inclusive multilateral system, or if a hybrid model, incorporating both bilateral and multilateral mechanisms, is the most pragmatic path forward. The effectiveness of these arrangements in a crisis often depends on the level of trust and cooperation among central banks, which can be easier to foster in bilateral or smaller multilateral groupings.

Future Challenges: Inflation Risks and Central Banks' Responses to Liquidity Shocks

Central banks face an increasingly complex environment, requiring them to navigate delicate trade-offs, particularly between maintaining their inflation-fighting stance and addressing financial stress. The recent past has demonstrated the inherent difficulty in predicting the precise nature of future shocks; for instance, the COVID-19 pandemic presented a real economy shock, unlike the financial crisis of 2008, and shifted concerns from deflation to inflation.

Inflation risks, driven by factors such as supply-side constraints and rising commodity prices, pose a significant challenge. For countries with weak central bank credibility, high exposure to exchange rate movements, and limited fiscal space, managing these trade-offs becomes particularly challenging, often necessitating reliance on a broader toolkit including foreign exchange interventions, macroprudential policies, capital flow measures, and international liquidity tools. The design of liquidity tools must evolve to meet these challenges, emphasizing operational flexibility, clearly specified objectives, and interventions targeted at critical markets to maintain financial stability.

Central banks are increasingly forced to navigate complex trade-offs in a volatile and unpredictable future. The experience of recent crises underscores the need for agile responses that effectively balance the imperative of price stability with the critical objective of financial stability. The inherent unpredictability of future shocks, whether originating from supply-side disruptions, geopolitical events, or novel financial vulnerabilities, means that central banks cannot rely on static frameworks. Instead, they must continuously adapt their tools and strategies, including the use of swap lines, to address evolving forms of liquidity shocks while mitigating inflationary pressures. This requires a nuanced understanding of market dynamics and a willingness to employ a flexible policy mix.

Are Swap Lines the Most Effective Tool for Crisis Management?

Central bank swap lines have undeniably proven highly effective in restoring equilibrium between dollar supply and demand during periods of severe market stress, thereby averting potentially catastrophic consequences for the global financial system. They have been particularly successful in relieving U.S. dollar liquidity stresses and addressing dislocations in foreign exchange markets. Their operational design allows for a faster and nimbler provision of U.S. dollars compared to traditional mechanisms like the IMF, which can be constrained by slower activation processes.

However, despite their proven utility, concerns persist regarding potential moral hazard, the inherent dependency on U.S. dollar liquidity they foster, and issues of fairness in their distribution, particularly the exclusion of many emerging markets. While highly effective, swap lines are not a panacea. They function most effectively as a complementary tool within a broader global financial safety net, working alongside IMF programs, regional financing arrangements, and other market-based instruments.

The evidence suggests that central bank swap lines are an indispensable, though imperfect, tool for rapid crisis management. Their ability to quickly inject liquidity and calm markets during periods of acute stress has been repeatedly demonstrated. However, their inherent limitations, including the potential for moral hazard, the reinforcement of dollar dependency, and concerns over equitable access, necessitate ongoing reform. To ensure a more resilient and equitable global financial architecture, continuous adaptation is required to address these drawbacks and integrate swap lines effectively within a comprehensive and inclusive framework of international monetary cooperation.

Conclusion

Central bank swap lines have evolved from ad-hoc measures to defend fixed exchange rates into a permanent and indispensable component of the global financial safety net. Their primary function is to provide critical cross-border liquidity, predominantly U.S. dollars, to foreign central banks, which then channel these funds to their domestic financial institutions. This mechanism is crucial for mitigating financial stresses abroad that could otherwise spill over and destabilize domestic U.S. markets, thereby safeguarding global financial stability and the flow of credit.

In conclusion, central bank swap lines are an indispensable, powerful tool for managing global financial crises, capable of rapid and effective liquidity provision. Albeit, their inherent limitations, including the risks of moral hazard, fostering dollar dependency, and perpetuating inequalities in global liquidity access, necessitate ongoing critical assessment and reform. To ensure a more resilient, equitable, and stable international monetary system, continuous efforts are required to address these challenges and integrate swap lines effectively within a comprehensive and inclusive framework of global monetary cooperation.

We know this is different from the series of research article shared, but if you made it up to this point, we are glad about that!

References

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1597320

https://www.federalreservehistory.org/essays/bretton-woods-created

https://www.bis.org/publ/work851.pdf

https://www.researchgate.net/figure/US-Dollar-Liquidity-Swaps-by-Central-Bank-2008-Total-Amount-Outstanding-USD-million_fig3_348882536

https://www.dallasfed.org/research/economics/2024/0521

https://cepr.org/voxeu/columns/central-bank-swap-lines

https://www.stlouisfed.org/publications/regional-economist/first-quarter-2020/changing-relationship-trade-americas-gold-reserves

https://www.elibrary.imf.org/view/journals/022/0009/004/article-A002-en.xml

https://elischolar.library.yale.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1480&context=journal-of-financial-crises

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1597320

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3571416

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3235226

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1441205

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4106664

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2955763

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3780794

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1361082

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4026409

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2299628

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3748491

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3748457

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2744528

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4155548

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3654322

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1369062

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4253443

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3909723

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1807117

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3931682

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1546650

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4423372

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3705195

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4908530

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3222673

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2504587

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4645744

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1952113

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2541531

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4475819

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2624514

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2624514

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1369057

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4509251

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4509407

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4457971

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4509325

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4509284

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4069931

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4069904

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2609451

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2766462